Rife with conflict, disaster, invention and sweeping change, there is not a century in history more fascinating and remarkable than the 17th.

In the words of J.P. Sommerville, University of Wisconsin history professor, the 17th century is “probably the most important century in the making of the modern world. It was during the 1600s that Galileo and Newton founded modern science; that Descartes began modern philosophy; that Hugo Grotius initiated international law; and that Thomas Hobbes and John Locke started modern political theory.”

At the same time, the century produced an unprecedented synergy of disaster, as described by Robert Burton in 1638: “War, plagues, fires, inundations, thefts, murders, massacres, meteors, spectrums, prodigies, apparitions…and such like, which these tempestuous times affoord…” And all of that during the first few decades.

Some historians believe the changes and difficulties of this century resulted in part from a global climate change. The “Little Ice Age,” extending from the 16th to 19th centuries, delivered a particularly cold interval in the mid-17th century.

England in the 1630s recorded great floods, widespread harvest failure, intense cold winters, wet and cold springs, and drought in summer so excessive that “the land and trees are despoiled of their verdure, as if it were a most severe winter.” Such conditions would have been seen in Ireland as well.

These natural forces so affected human activity as to upset the existing social, economic and political equilibrium. People facing cold, famine, and grave uncertainty are likely to behave in more desperate manner.

Ireland in particular faced considerable unrest as the lands, traditional clans and centuries-old way of life were forever altered.

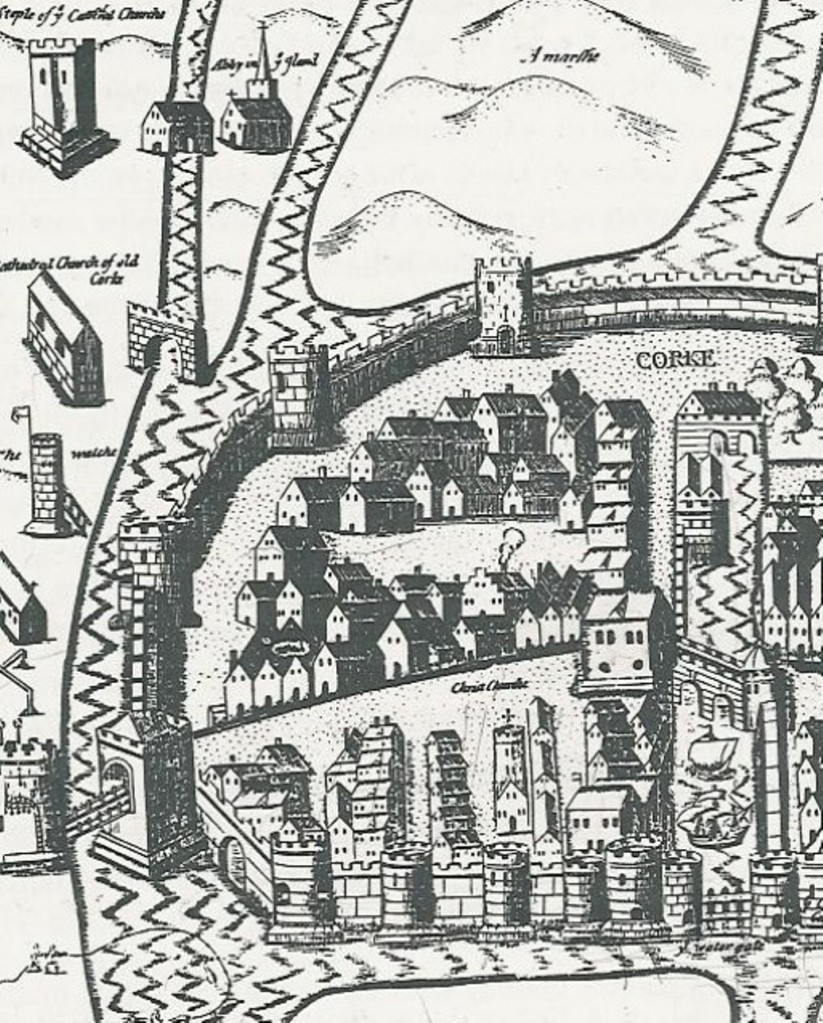

Life in Ireland

In 1603, Queen Elizabeth I died, leaving her throne and kingdom to James I. Her military forces in Ireland had delivered a crushing blow to end the Desmond rebellion in the southwest province of Munster.

The English saw Ireland as underutilized and ripe for exploitation. They sought to improve on Irish farming methods by settling their own more efficient farmers, and thereby increasing crown revenues.

The Earl of Desmond was among the Irish gentry who held castles, manor houses and vast tracts of land. They were mostly of Norman or Saxon roots, descending from distinguished families or clans who had obtained grants from Henry II in the 12th century. They resented the crown’s efforts to take control of their long-held dominions and displace their Irish tenants: typically subsistence farmers who paid rents either in food or in coin from the goods they sold. Often these tenants lived in one-room houses constructed of mud and grass, with no windows and a single door that served as both the entry and chimney.

Lord Deputy Arthur Grey seemed to defeat Queen Elizabeth’s purpose with his cruelty and scorched earth tactics. He left the province devastated, little more than a wasteland that would require years to recover, and was later removed from his position for excessive brutality—but, he had cleared the way once and for all for English settlement.

In a land already compromised by drought, the remaining Irish faced terrible famine, plague, disease, homelessness and oppression. Lands that had been owned and passed down through generations by traditional clans, especially Irish Catholic, were confiscated and granted to English military officers as reward for their service. Survival for the Irish was tenuous and choices were few. Some restoration took place in the coming years, but a fury simmered below the obedient surface.

In 1625, Charles I succeeded his father and extended his policies, filling his treasury through increased taxation and monopolies to his favorites, and expanding plantation in Ulster. When civil war erupted in England, Irish clans welcomed the distraction. They organized and rebelled again, retaking confiscated lands and ousting the English settlers, often violently.

When Parliament was victorious in the civil war, it took control of England and all of its business, and shocked the monarchies of the world by executing King Charles in 1649.

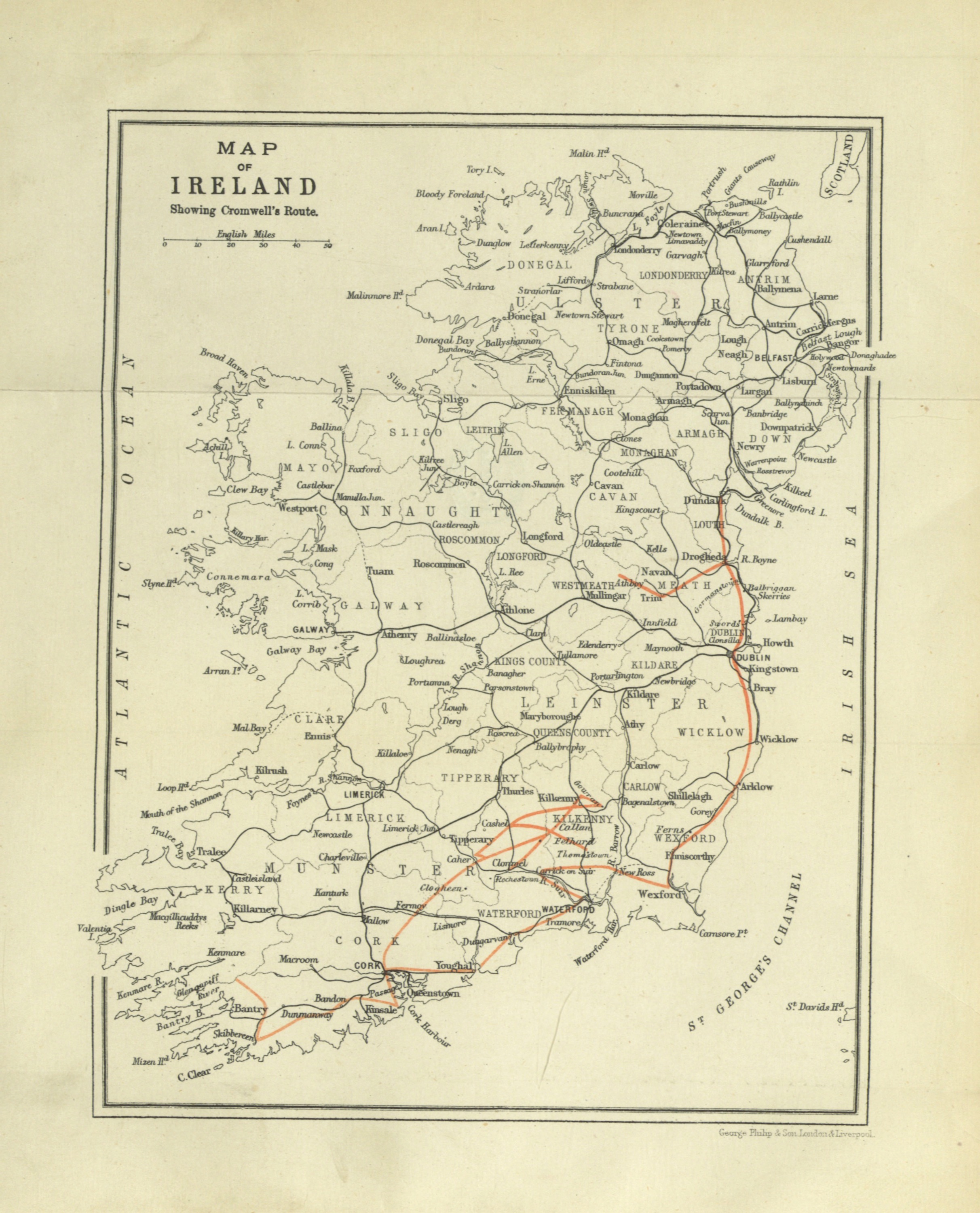

Parliamentary army leader Oliver Cromwell now turned his attention to Ireland, cutting an unrelenting swath of brutality, destruction and death across the island. Towns were leveled, people massacred, and terror wrought with full force. One estimate claims 618,000 Irish deaths from fighting or disease—an astounding 41 percent of the pre-war population.

Surviving Irish were relocated to rocky hills that served better for grazing sheep than growing crops. Some joined armies and fought in foreign wars; some became pirates. Some were sent to workhouses where they likely died; some escaped to colonies in America. Cromwell deported many to the West Indies where they perished from slave labor and tropical disease.

Irish Catholics were forced out of the Irish Parliament, while Catholic Mass and the Irish language were outlawed. Catholics were banned from holding office, Catholic clergy were expelled from the country, and Catholic landowners were stripped of their properties. An estimated one-third of the Irish-Catholic population was killed or deported.

On the heels of this work, Cromwell was elevated to “Lord Protector,” England’s uncrowned king, and he established his famed Commonwealth. Oppression of Ireland was severe and would be seen by historians as genocide. But by the time of Cromwell’s death in 1658, England had tired of his Puritan influences, and his son proved a weak successor. Charles II was brought back from his exile in France and monarchy was restored.

While somewhat kinder and more tolerant toward the Irish who had supported his return, including the Earl of Ormonde who had led the royalists in the Irish Confederacy, the plantation of Ireland continued. Known as the Merry Monarch, Charles II restored some of the gaiety that had been lost to England, and smoothed the way for new thought, invention and discovery in the latter part of the century as the Age of Enlightenment was dawning.

(Geoffrey Parker’s Global Crisis was a valuable source for this post)

The Prince of Glencurragh is set in 1634 prior to the great rebellion of 1641. It is a stand-alone prequel to my first novel, Sharavogue, which won first place for historical fiction in Florida’s Royal Palm Literary Awards. Both books are available on amazon.com and barnesandnoble.com. Visit my website for more info, at nancyblanton.com.

The Prince of Glencurragh is set in 1634 prior to the great rebellion of 1641. It is a stand-alone prequel to my first novel, Sharavogue, which won first place for historical fiction in Florida’s Royal Palm Literary Awards. Both books are available on amazon.com and barnesandnoble.com. Visit my website for more info, at nancyblanton.com.

Aengus O’Daly is what every good storyteller should be: observant, thoughtful, and inspired by love. He tells the story of his best friend Faolán Burke, both valiant and true, who tries to restore the world of his father’s dreams.

Aengus O’Daly is what every good storyteller should be: observant, thoughtful, and inspired by love. He tells the story of his best friend Faolán Burke, both valiant and true, who tries to restore the world of his father’s dreams.

Sharavogue is the award-winning novel of 17th century Ireland and the West Indies, available now on

Sharavogue is the award-winning novel of 17th century Ireland and the West Indies, available now on

Why not embark on an adventure in Irish history? Sharavogue makes an excellent gift for yourself or someone you know who loves historical ficion. Find it at

Why not embark on an adventure in Irish history? Sharavogue makes an excellent gift for yourself or someone you know who loves historical ficion. Find it at