Enemies and Kings

/Having recently finished reading Hilary Mantel’s latest historical novel, The Mirror and the Light, the last book in her famous Wolf Hall trilogy, I am thinking of the comparison to a similar situation that took place in England a century later—and how history does repeat.

Thomas Cromwell, 1st Earl of Essex (1485 – 1540) is the protagonist in Mantel’s novel, written entirely from Cromwell’s perspective. This Cromwell (not to be confused with Oliver Cromwell who came along much later) is best remembered as the lawyer who engineered King Henry VIII’s position as head of the Church of England. This allowed the king to annul his first marriage to Katherine of Aragon, and to then marry Anne Boleyn. From there, Cromwell ascended to higher posts and became chief advisor to the king, who later signed the order for Boleyn’s execution, and would sign the same for Cromwell just a few years after.

Cromwell’s ascent and fall are similar to that of Thomas Wentworth, 1st Earl of Strafford (1593 – 1641), best remembered as the “scourge of Ireland” by some, and by others as chief advisor to King Charles I prior to the Civil Wars. Charles signed Wentworth’s execution order as well, and both kings ultimately regretted their decisions.

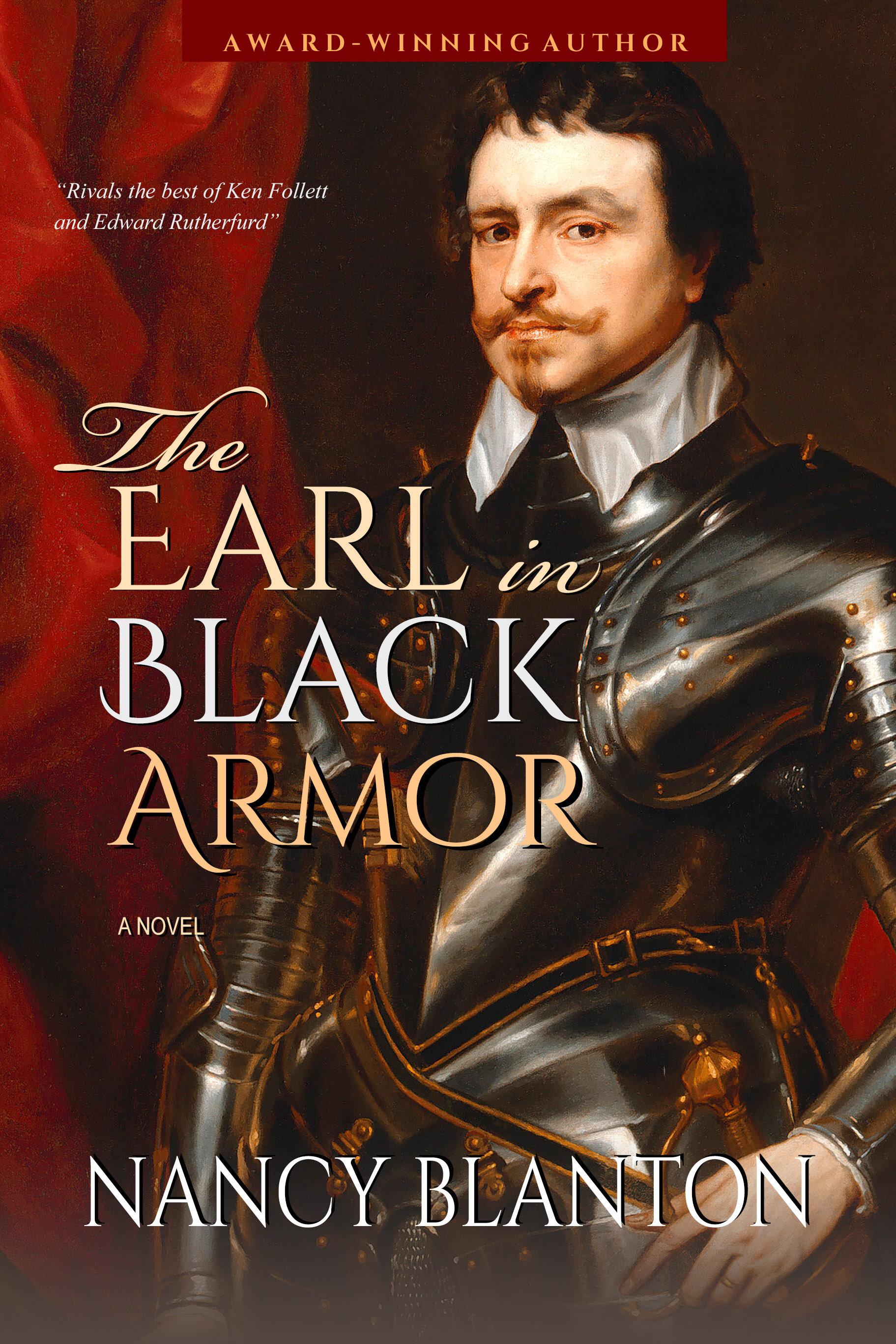

I spent a great deal of time studying Wentworth as I wrote my third historical novel, The Earl in Black Armor. The comparison of the two men became quite clear, along with a recognition of the changes that would one day alter this recurring path.

ORIGINS & MENTORS

Cromwell was born a commoner, the son of a blacksmith. He literally fought his way up from poverty and the brutal streets of London to become a lawyer. Conversely, Wentworth came from one of England’s wealthiest merchant families, learned the law and served in Parliament. However, neither of the two men descended from noble blood, which meant that both would know discrimination, jealousy, hatred and betrayal from English nobleman who resented their hard-earned royal favor and resulting power and influence.

Both men were mentored by and had close relationships with clerics, particularly those closest to the kings. Cromwell was a disciple of Cardinal Thomas Wolsey—another famous historical figure—who had advised the king in all matters of state, but fell from grace when he failed to obtain the king’s marriage annulment from the Pope. Wolsey was accused of treason but died from natural causes before he could be officially charged.

Wentworth aligned with William Laud, the Archbishop of Canterbury, through a shared belief in the uniformity of religion and concerns over the dangers of Puritanism. Under a Puritan-controlled Parliament, Laud was accused and imprisoned for treason which could not be proved, and was then executed anyway under the Bill of Attainder.

GREAT AMBITIONS

Both Cromwell and Wentworth obtained high offices and garnered considerable wealth under the kings’ favor. Cromwell had more power than any other servant to the crown in England’s history at that time, from domestic administration to international diplomacy. Thomas Wentworth went from Lord Deputy of Ireland to become the first Earl of Strafford (obtaining his long-sought nobility), and was the king’s leading advisor in the Bishops wars. Both Cromwell and Wentworth were made Knights of the Order of the Garter, the realm’s highest honor, for chivalry.

Both men, for a time, had the ear and the trust of their sovereign to the exclusion of most if not all others. Both also, were known for their arrogance and rigid mindsets, that alienated many potential supporters.

ENEMIES

In turn, the ascendance and behavior of these men created for both the cadres of powerful enemies who opposed them. These were the people who begrudged the wealth, influence, and policies that conflicted with their own interests—often the ancient noble families who made their fortunes by means of royal favor and corruption.

For example, Cromwell oversaw the dissolution of the Catholic monasteries, in the process enriching the king and himself, but taking from others valuable lands and sources of income. Wentworth oversaw the surrender and regrant operation in Ireland, and the Commission of Defective Titles, which provided rather stealthy means to take land away from hereditary owners and give it to English plantation settlers.

These enemies eventually secured the downfall of both men.

Cromwell lost favor with Henry VIII when he arranged the king’s disliked marriage with Anne of Cleves. With his position weakened, Cromwell was betrayed by his own protégés and crushed by angry nobles. He was executed under the Bill of Attainder and the king’s consent.

Wentworth was attacked by a strong Puritan-led Parliament who saw him as the only barrier to complete control over the king. Unable to prove treason against him by law, he also was executed under the Bill of Attainder, and the signature of King Charles I.

THREATS

In Henry VIII’s time, there were two main threats to the English crown. First, the foreign countries, i.e. France and Spain, who sought to restore the Catholic faith on English soil. And second, the ancient noble families who still believed a Plantagenet descendent belonged on England’s throne, rather than a Tudor.

However, by the 17th century, the Stuart Dynasty faced far greater threats that were more difficult to fight, such as philosophy, science, literacy, and church reformation—all that managed to change the way people saw their lives and experienced their world.

The 17th century was in fact a time of great discovery, and people did change—from believing the sun revolved around the earth to vice versa, for instance, and from believing the heart’s purpose was only to heat the blood, to understanding its central function for the circulation system.

The greatest threat to King Charles’s throne was not the freedom of religion, which he fought against and lost in the Bishops Wars. It was the dwindling belief in the Divine Right of Kings—the concept long-held throughout Britain and Europe that kings are chosen by and directly instructed by God.

CHANGE OF MIND

Scholars say what truly distinguishes man from beast is the ability to think, learn, and change our beliefs over time. Two specific changes would alter the path of history taken by Cromwell and Wentworth. First, a new belief was now dawning that kings are as fallible as any other human being, and that every person has access to God through prayer. This change undermined the power of the monarchy, and opened the doors to rebellion, revolution, and collective, represented decision-making.

The second change has taken a good while longer. That is, the demise of the Bill of Attainder, which allowed authorities to legally arrest and punish a person for a crime without any real proof or trial. The bill was last used officially in 1798 to arrest Lord Edward Fitzgerald for leading the Irish rebellion of that year. He died not from execution but from wounds obtained in resisting his arrest. Sources say the bill was abolished in Britain by the Forfeiture Act of 1870. But another source says Winston Churchill had intended to use it against Nazi war criminals, and only backed down under political pressure.

Today, England and the U.S. each have a constitution and bill of rights that protect citizens from such unfair and inhumane practices. But we do still have political conflicts, and though they generally don’t result in executions, those who rise high and then fall from favor have experienced what we call character assassination, and then those people tend to disappear from the public eye. So perhaps in its own way, history does, in fact, repeat.