In the time of Thomas Wentworth, 1st Earl of Strafford, 1593 – 1641

/Thomas Wentworth by Sir Anthony van Dyck

Just before the turn of the 17th century in 1593, Thomas Wentworth was born in London, into fortune, property and prestige. Queen Elizabeth I still reigned, and the bloody Nine Years War raged on in Ireland.

By 1614 when his father died, Wentworth inherited the great Wentworth Woodhouse of Yorkshire—by the 18th century the largest of England’s country houses—plus two other estates and vast business holdings to keep things running. In addition to income, such land ownership commanded power and respect. Truly, Wentworth already had everything and more than most people might desire in life.

But he sought more than anything what he did not have: a royal title. An earldom. It would come at the greatest cost.

His ambition led him to politics. He started law school in 1607, and in 1611 he was knighted. He married an earl’s daughter. As a principal landowner he quickly became Yorkshire’s representative in the English Parliament.

King Charles I by Sir Anthony van Dyck

In 1625, Charles I ascended to the throne. The following year Wentworth became High Sheriff of Yorkshire, and in 1628 he returned to Parliament to become one of the most vocal supporters of the Petition of Right, which attempted to curb Charles’s non-Parliamentary taxation, forced billeting of soldiers in people’s homes, imprisonment without cause, and the use of martial law.

Wentworth showed himself to be smart, reasoning and persuasive, with strong leadership abilities. He became President of the Council of the North. He joined Parliament’s dispute with King Charles I over subsidies to support the Thirty Years War effort, and stood against the king even to the point of imprisonment for refusing to pay his “forced loans.”

But here is where he made his first dangerous turn. The king invited Wentworth to join the Privy Council: to sit at the king’s table with titled courtiers and advise the king on decisions to run the commonwealth. It fed Wentworth’s deepest ambition. It was an offer he could not refuse. But it branded him as a turncoat to his fellow Parliamentary members. He had been seduced by power.

Wentworth turned from fighting the king’s arbitrary use of power to being a staunch supporter of the Divine Right of Kings. Charles had picked up his father King James I’s torch for this the long-held belief that monarchs were chosen by God, had a direct connection to God’s word, and therefore should always be trusted to do God’s will and make decisions for the highest good, guided by God’s hand.

At this time in history, however, people had seen many rulers supposed to be God’s designees on Earth who made very poor decisions. They had recognized greater access to their own religion through Calvinism and could read the Bible themselves. The printing press, nearly 200 years old, was demonstrating the considerable powers of mass communication. And the Divine Right was under fire.

By 1629, Charles grew tired of arguing with Parliament for what he wanted, and having to ask for his subsidies. He decided he no longer needed Parliament at all. He adopted “self rule,” which became known later as the Eleven Years’ Tyranny.

In 1632, the king appointed Thomas Wentworth to be the new Lord Deputy of Ireland. Although distant from the king’s court, it was a very powerful position in a time of sweeping change.

Ireland had been settled by the Anglo-Normans since the time of King Henry II in the 12thcentury, and from that time great and powerful clans had developed and intermarried with the Irish, such that they became accepted “Irish” clans. Until the time of Henry VIII, they ruled their realms autonomously.

The Desmond Rebellions of the 16th century began when Henry named himself king of Ireland, and tried to exert his authority over all the clans, starting first with plantations in fertile Munster. They ended with Irish defeat just before Elizabeth I died in 1603. Several clan leaders remained loyal to the king, yet Ireland remained resistant and challenging to oppressive English rule. To English adventurers, Ireland seemed like a plum that waited to be picked.

If Wentworth’s appointment to Ireland had been orchestrated by other courtiers eager to get him out of the running for the lucrative job as the king’s treasurer, no matter. Wentworth saw great opportunity, and planned to be the most effective viceroy the king had ever seen.

At this point his first and second wives had died. Wentworth had secretly married the 18-year-old daughter of a Yorkshire neighbor, and sent her ahead to Ireland to start preparing their home. Meanwhile he studied and learned, preparing for a long-term and “thorough” effort to make Ireland a profitable venture for the king. He did not set foot on Irish soil himself until July of 1633, with a huge retinue including 30 coaches of six.

And the first task on his list, after losing to pirates the £500 worth of wardrobe that he had shipped ahead, was to get control of the Irish Sea and secure Ireland for trade.

Laureys a Castro – A Sea Fight with Barbary Corsairs. Wikimedia Commons, public domain

More than half of the king’s subjects made their livings from the sea, whether collecting fish, oysters, pearls, eels, gulls—anything they could eat or sell—or operating small craft and large merchant ships for moving passengers and goods. At the same time, Algerian pirates were notorious for robbing ships of their cargo, and robbing or abducting passengers and crew for ransom or to sell as slaves. Wentworth quickly took control by installing trusted captains to patrol the Irish Sea, and by rooting out corrupt officials who took bribes from the pirates and pocketed money intended for their crew’s provisions.

Once installed in Dublin Castle, Wentworth began a mission of “thorough,” intending not only to establish law and order for common people, but to root out corruption among the nobles, such as the Great Earl of Cork who’d been enjoying a healthy portion of the tithes from the church at Youghal. He would support the growth of Protestant religion while limiting the political power of Catholics. He would invest in new industries like the wine trade, linen and tobacco. And he would continue in the king’s interest the spread of English plantations.

Wentworth saw plantation as a benefit to Ireland, believing native Irish did not understand how to wring the greatest productivity from their lands, and more industrious English (Protestant) settlers would demonstrate the most efficient and lucrative practices. But it was met with great resistance, and the underlying goal was far from altruistic.

Wentworth devised a plan by which, instead of the crown just taking lands, the existing landowners would happily surrender their lands to the king in order to have them returned with clear and legal titles—minus, of course, the 25 percent of the best lands that Charles would keep for himself. The goal was to shift, over time, the majority of land ownership from Catholic to Protestant. The result of this process was considerable unrest, as the nobles lost income and Irish families were turned out of traditional homelands.

Over several ensuing years, Wentworth methodically and relentlessly carried out his plans, implementing the king’s divine right, arrogantly establishing absolute rule, and enriching himself along the way. His tactics and lack of political finesse made him many powerful enemies in all corners of his life. By the time of the Bishops Wars (1639-40) against Scotland—the king’s attempt to enforce his own religious practices upon the Puritan Scots—Wentworth became the king’s primary advisor and received his coveted earldom. He was named Earl of Strafford in 1640.

And then, when the wars were lost, he became the king’s scapegoat.

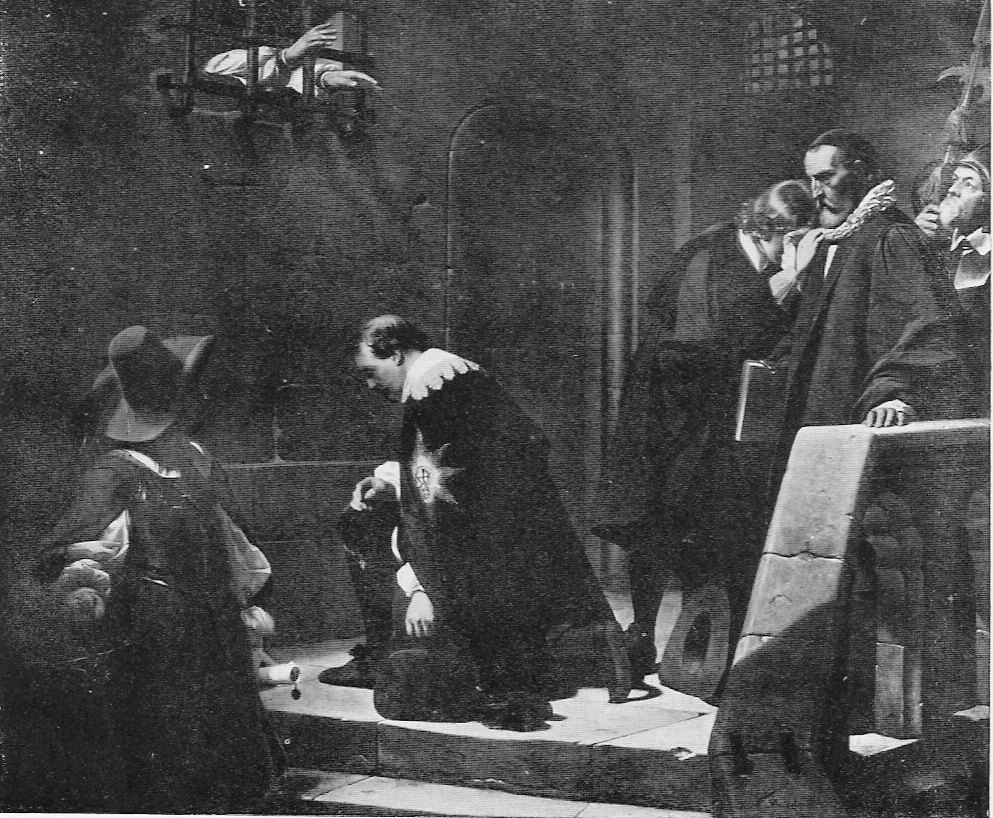

Wentworth receives final blessing from imprisoned Archbishop Laud, by Paul Delaroche, 1835 Wikimedia commons, public domain

Parliament was called because money was needed to pay the Scots army under terms of the treaty. Parliament then impeached Wentworth—fueled by his enemies in Ireland. And when, angered over the country’s bankruptcy, the members were unable to prove treason against him, they dusted off an ancient, unused but still available tool, the Bill of Attainder, which required no need of proof to execute a man accused of high treason. King Charles, in his classic, two-faced, self-serving behavior, signed the death warrant for his most loyal servant.

Wentworth, having achieved his goal and reached his zenith of wealth and power, was beheaded by Parliament in May of 1641.